The Science of Food and Cookery (H. S. Anderson, 1921) is fascinating on a number of levels.

One is that this is a vegetarian cookbook, long before the hippies made vegetarian cookery more popular in the 1960s and '70s. Another is that this copy is a library book from The Hotel and Restaurant Department of the City College of San Francisco. Perhaps most surprising of all is that this book was in circulation until at least September 20, 1996-- the last due date stamped on the date slip in the back of the book! I briefly imagined that the book was in circulation for 75 years, but that's impossible, as the school didn't open until 1935, and then it was named San Francisco Junior College. It didn't become City College of San Francisco until 1948, so this book was already well over 20 years old by the time it became a library book-- perhaps highlighting how few options there were at the time for people who wanted vegetarian cookbooks?

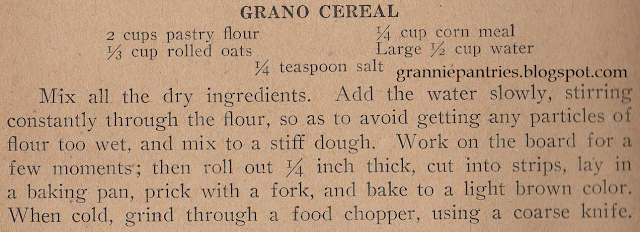

Sometimes, all this work for vegetarian options seems kind of needless. For instance, cooks were expected to make their own homemade breakfast cereal.

I'm not sure why, as commercial cereals were definitely available by this time, and I'd imagine a simple bowl of shredded wheat would be more nutritious than something based mostly on pastry flour and corn meal. (Plus, it wouldn't require all that mixing, rolling out, cutting in strips, baking, and sending through a food grinder!)

You might think some coffee would be a reasonable accompaniment to cereal, but it's not so simple. While coffee is vegetarian, it's still not allowed because it "cheats the body by producing sleeplessness" and "Its use is often followed by palpitation of the heart and indigestion." Instead, the book's audience would have to fabricate "coffee" out of things that were clearly, well, not coffee. Now I know for sure that soybean coffee long predated the version in 1972's Natural Cooking the Prevention Way:

And if cooks don't happen to have access to a big store of soybeans, the book offers more specifics on how to make Homemade Cereal Coffee than Cookbook United States Commemorative 1776-1976 did.

Still, though, it often makes sense that this book expects cooks to put a lot of effort into the dishes. Home refrigerators were not yet a thing, so it took a lot of effort to preserve food. While the book has plenty of recipes for home canning, I was more interested to learn how home cooks preserved eggs (a common ingredient in the recipes for both their protein and their binding abilities). For those who might not have regular access to fresh eggs (or wanted to stock up when the price was low), the book offers the "Water-Glass Method" to preserve fresh eggs for up to a year.

I was interested to know that the preservation in silicate seals the pores in the shell so tightly that it needs to be pricked before boiling, and I was even more interested to see that this type of preservation is still used!

The most difficult part of being a 1920s vegetarian might have been finding substitutes for meat in a culture that saw meat and potatoes as the necessary center of the plate. It's not like cooks in 1921 could run out to the grocery store for packages of Beyond, Impossible, or Gardein. Instead, they got to stay home and make things like Nuttose.

Yum! Nothing like nut butter thinned with water, then thickened with a slurry of tomato pulp, flour, and cornstarch and cooked for 2-3 hours... You may note, though, that the name "Homemade Nuttose" implies that it could be bought. That's right! John Harvey Kellogg invented the original Nuttose and started selling canned versions of it in 1896. (Here's an ad from 1898.) I imagine it was still pretty hard to find with the limited grocery options of 1921, though, and the homemade version probably cost less anyway.

If Nuttose didn't cut it for old-timey vegetarians that might be craving something meaty, the book also offers recipes with the meaty-sounding "fillet" in their names, like these Olive Fillets.

I'm really not sure how a bread triangles enclosing a filling of chopped olives, onion, and parsley before being baked under a thin cream-tomato sauce count as fillets, though. This recipe still seems like less of a stretch than the Cereal Fillets, though.

Isn't this basically just mush? Yes, the cornmeal is cooked in milk instead of water so it has a little extra protein, and it's breaded before the second cooking (baking rather than frying, "because hot fats not only coat but intimately penetrate the food with which they are cooked"! 😮). I guess the breading is supposed to make it look more fillet-like, but come on. This is barely-disguised mush. Even the recommendation to "Serve with maple sirup or jelly" seems like an admission that this is mush rather than a meat-like fillet.

I hope you're as fascinated by this 100+-year-old window into vegetarian cooking as I am, because I haven't even showed you the casseroles, or the toasts, or the aspics! Stay tuned.

That is an amazing technique for preserving eggs. It sounds like a stronger version of the natural coating eggs have to preserve them. I know that there are a lot of countries where eggs aren't refrigerated because they don't wash the coating off like we do, but it sounds like these stay better for much longer. I wonder if there is a flavor change. The description didn't mention one, but that may be a purpose omission.

ReplyDeleteIt might be like other shelf-stable goods-- safe to eat for a long time, even after the expiration-- but you're going to notice a difference after a while. Just speculation on my part though, as I'd never even heard of the technique before.

Delete